Aspire Thought Leadership! Wondering about strategy in supply chain governance? Find out more on how fortune 500 companies use this approach. Come rig

Most brands do not have a clear upstream visibility on supply chain governance. End-to-end visibility is a challenge: a single shipment might have over 200 interactions with more than 25 people! The requirements for supply chain visibility vary greatly depending on the industry, but for most companies today, traceability and visibility requirements include more information in addition to the physical location and status of components: quality controls, material certifications, supplier information, legal, and safety certification. Understanding how the supply chain works is the first step in the direction of establishing a branded supply chain. The supply chain is a crucial part of any organization’s functionality. It’s invaluable for marketing and brand executives to consider the delivery of the right product to the right place at the right time as part of the brand promise. In the following part, an illustration of how the supply chain can be designed and managed is presented.

Supply Chain Governance Models

According to a framework by Boston Consulting Group (BCG) as exhibited below, supply chain models can be designed according to two dimensions: need for modularity and for coordination.

|

| Supply chain governance |

- Modularity. The concept of modularity refers to the way that a product design is decomposed into different parts or modules, and it helps explain different product architectures. Modules are units in a larger system that are structurally independent of one another, but work together [mindfulness in the workplace]. Most desktop computers are modular because they have easily removable and upgradeable parts. A modular product or process architecture enables a company to create different offerings for different customers by selecting a particular set of modules that match market demand, and then linking them together to create a unique offering. For instance, the modular design in apparel breaks down the clothes into different parts, and each part as a module can be disassembled to restructure with others. Garment is no longer seen as a product, but as a result of multiple modules. These modules can be integrated according to endless solutions. In terms of manufacturing, modularity requires maintaining independence between components and processes in different modules, encouraging similarity in all components and processes in a module, and maintaining interchangeability between modules. There are degrees of connection, thus there are gradations of modularity. The system as a whole must therefore provide framework, an architecture, which allows independence of structure and integration of function [strategy in supply chain management].

- Need for coordination. Coordination is about synchronizing the functions of various modules, phases, activities, or sections for achieving organizational goals with minimum effort. It provides unity of action in the pursuit of common purpose. The greater the interdependence among parts, greater is the need for coordination.

Combining the two dimensions, four supply chain governance models emerge.

- Vertically integrated model. The company performs all key activities within the organization. Benefits are growth in market power, economies of scale and increased efficiency, and reduced uncertainty. Integration is an option for many industries and business models [business agility]. The supply chain of luxury brands such as Louis Vuitton, Hermes, Tods, Bottega Veneta in leather goods is vertically integrated to guarantee of the best possible quality and train and retain the best craftspeople. Tesla has a vertical integrated supply chain because of the innovativeness of its product with a fully operational plant in California and a giant battery factory in Nevada, USA. In the arena of food as consumers demand further transparency of growing practices and animal treatment, Walmart has created its own supply chain for Angus beef and milk processing, whereas Costco invested in a poultry production facility in the USA. Tiffany sources all its gold from a mine in Utah and uses recycled gold. Vertical integration is not an option when the quantity that is needed from the supplier is not on sufficient scale, components are hardly available, the competencies required are very different among activities, and the vertically adjacent activities are in different industries.

- Hierarchical supply chain. The company outsources certain activities to external suppliers. In this model, products are highly customized, usually tailored to buyer’s needs, and there is a strong interdependency between the buyer and supplier. Usually, suppliers do not work for other clients, have no outside options, and make investments according to the buyer’s specifications. Flexibility, innovation, and collaboration are potentially the most significant benefits of this model compared with vertical integration. The supply chain of fashion brands such as H&M or Nike are examples. Differently from vertical integration, in this case, the need for coordination is high as suppliers are external. The American fashion Group VF owns and operates 24 world-class manufacturing sites and contract with more than 1,000 supplier factories to produce its products. Through the Responsible Sourcing program, they share their values-driven internal manufacturing model with these contract suppliers to positively influence the supply chain and the industry. Within a hierarchical supply chain, means of coordination can be contractual and/or relational. Contractual governance is based on binding formal agreements that specify obligations and roles of exchange partners. These agreements determine compulsory deliverables, monitoring policies, and noncompliance penalties. Relational governance, in contrast, refers to trust-based social and moral norms. It is characterized by shared values, open communication and exchange, coordinated action and joint problem solving, as well as flexibility. Contractual and relational governance mechanisms can be complementary, and are therefore often used simultaneously in practice. Although usually large companies can coordinate the entire network and align the incentives for all the participating players, there are situations where the coordinator role can be shared with a neutral third party, a trader such as Li & Fung in fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG), which can orchestrate a portion of or the entire the supply chain coordination.

- Open-market model. The company selects and buys the required components from independent and uncoordinated providers in an open, competitive market. In this case, products are standardized (e.g., commodities), capabilities in the supply base are high, there are low switching costs for both buyer and supplier, no (or little) transaction-specific investments, relatively easy to substitute to options.

- A business ecosystem. In case product modularity and need for coordination among modules are both high, the company needs to coordinate with other, largely independent economic and institutional players in order to create a coherent offering. The idea is that each entity in the ecosystem affects and is affected by the others, creating a constantly evolving relationship in which each entity must be flexible and adaptable in order to survive. Business ecosystems have advantages in terms of speed, market responsiveness, and show resilience in turbulent times continuously adapting their offering to a changing customer base. This model is widely used in digital businesses, but increasingly adopted by other industries [digital transformation strategy]. Apple leads a large ecosystem of suppliers, app developers, hardware add-ons companies, retailers, and users [retail pricing strategies]. Most of what happens within the ecosystem is guided by frameworks that Apple creates. Uber is an ecosystem based on mobility; Apple, Fitbit, and Garmin created an ecosystem focused on fitness and apps. The fashion platform Farfetch has started to serve smaller fashion boutiques with an all-encompassing service approach to e-commerce. Today, it is a global platform for luxury fashion, connecting creators, curators, and consumers, operating with a modular end-to-end technology platform built to connect the luxury fashion ecosystem worldwide.

Today, the word ecosystem is widely used to identify contexts where heterogeneity of actors and evolving multilateral relations are key. Given this ambiguity, we want to dive deep into the concept and offer a further conceptual frame to better understand this model. In fact, business ecosystems intended as networks based on high modularity and high need for coordination can be further segmented in terms of size and governance obtaining two dimensions [

artificial intelligence in business].

- A macro dimension (country or industry level). A macro-business ecosystem is led by a group of organizations and their overarching goal is broad and focuses on helping an industry or a group of organizations that have a common interest. It shows up through initiatives such as industry standards or lobbying or knowledge management and diffusion. Typical examples are industrywide associations, and we will present the case of the Italian Tanners’ Association.

- A micro dimension (company level). This is a captive system where the brand becomes the control tower and gravitational center of a selected network of actors, orchestrating many of the actions taken by the institutional and supply chain partners, playing the leading role in building and maintaining trust, efficiency, and collaboration among all parties. We will present the case of the Hong Kong-based Li & Fung Group.

Why are ecosystems the future of supply chain Governance?

The evolution toward purposes-led organizations requires a similar evolution in the process of value creation end-to-end [

value matrix]. Many of the world’s leading brands in FMCG industries such as fashion and luxury have an integrated or a hierarchical model with directly owned and operated stores and the internalization or control of suppliers. However, an evolution of supply chain models toward ecosystems will probably be in many industries required for three reasons.

- Innovation and future growth will require entering new channels, markets, and product categories with the need of a much wider range of ideas, expertise, and knowledge than the one that can be effectively developed in-house; co-design, co-creation, and co-buying are opportunities where, for instance, fashion and design companies can leverage network effects.

- A firm that takes an action without understanding the influence on the wider system it belongs to ignores the reality of the networked environment in which it operates with all related effects in terms of reputation. Linearity of decision making and operations with defined consequences and siloed information is no longer relevant in the current world. From linear models supply chains are evolving into interconnected environments, where even minimal change ripples across the whole ecosystem. Forward-looking supply chains plan toward this transition.

- As it happens in nature, systems with higher diversity tend to be more stable with greater resistance and resilience in the face of disturbances and disruptive events (the so-called network effects). Stability as a consequence of heterogeneity within the business ecosystems can be considered an advantage in terms of risk management, where multiple players contribute to the supply chain enhancement by diversifying market risk. It is clear in the example of Covid-19 pandemic’s disruptive effect on supply chains relying on one single provider located in a highly affected country.

The more brands are required to manage their image and reputation in a turbulent environment, the more they must adopt a new paradigm and vision about their supply chain network. They have to think that competition is not against their suppliers but, on the contrary, brands are competing against other brands and retailers with their own networks. If the old approach was that the stage of the chain was separate and adversarial, today supply chains optimization requires a high level of trust and partnership.

The case of the Hong Kong-based trader Li & Fung

The Li & Fung case presents all the challenges and complexities connected to the role of supply chain orchestration. The Hong Kong-headquartered company convenes the global supply chain creating customized, end-to-end supply chain and logistics solutions for brands and retailers in FMCG.

Building an ecosystem

In the 1950s, a UN trade embargo on China prodded companies in Hong Kong to begin manufacturing textiles, and so Li & Fung started exporting apparel, presently making up the majority of their business. Over the years, it has evolved from a trade broker between the West and China into a multifaceted coordinator of manufacturing of high-volume, time-sensitive consumer goods for American and European brands such as Walmart and Nike. Today, the once-small trading company is one of the largest trading and logistics businesses globally. Although it maintains a network of around 17 thousand employees in more than 230 locations in over 50 economies, it does not own any factories. The company indirectly provides employment for more than two million people in its network of suppliers, but only a fraction of these is on Li & Fung’s payroll. Li & Fung rather coordinates with independent suppliers using financial incentives and an elaborated benchmarking system, which allows Li & Fung to track the performance of each player in the supply network.

Li & Fung’s business model holds remarkable resemblances to that of Uber’s. Both are ecosystem-based business models; neither companies directly create the product that their customers use [

customer value proposition]. Instead, they coordinate interaction among groups.

While Uber connects drivers with people needing rides, Li & Fung coordinates the production of goods via a vast global network of factories to arrange for private-label manufacturing, primarily for Western apparel merchants. Li & Fung not only connects its providers, which handle product development, sourcing, production, and shipping, but also

offers solutions from partners enhancing the full value chain: from factoring and credit financing to digital solutions (such as virtual sampling, procurement platforms, and e-commerce) as indicated below. The ecosystem works through a range of coordination mechanisms such as licenses, joint ventures, direct investments and strategic alliances [

strategic pricing]. Therefore, Li & Fung is positioned as a “control tower”, a unique orchestrator of capabilities and an aggregator of solutions managing the network at a macro level and not in the day-to-day operations.

|

| Supply chain governance framework |

Not only the Group has built up a model where technology and automation support the continuous innovation engine, but they also created a community. As for every partnership-based model, trust and integrity are the cornerstones of their long-lasting relationships and essential in fostering loyalty and teamwork. The company cultivates supplier trust and motivation by visiting them several times during the production process to ensure that quality standards are met and it offers suppliers continuous training to develop the knowledge and skills required to succeed and mitigate their business risk.

Making the ecosystem evolve: the supply chain of the future

The key to success of the original Li & Fung model was the ability to operate without borders in a flat world. As the global trading environment has been becoming highly disruptive and unpredictable, with change often defined as exponential, the Li & Fung model has been severely affected and challenged, showing all the complexities connected to the role of global supply chain orchestration. Between 2004 and 2014, Li & Fung’s turnover more than tripled to nearly $20 billion; since then, a business model built on big orders for big companies in a flat world has been losing sales, margins, and market value.

Causes can be summarized as follows:

- if in the last 40 years, the whole supply chain was optimized for cost; today, most customers optimize the supply chain for speed. Reducing production lead time and improving speed-to-market becomes mandatory;

- traditional margins for trading activities have been reducing in a context where companies are sourcing directly or vertically integrating manufacturing activities;

- due to rising costs and conflicts, many companies are now diversifying away from China and pursuing a more diversified global sourcing strategy;

- retail and digital disruption continues at a very fast pace with competitors as Amazon and Alibaba are affecting the traditional merchant’s business; and

- finally, the COVID-19 pandemic has caused wholesale disruption of both demand and supply.

The supply chain of the future will be a multidimensional world where brands, retailers, and suppliers, can seamlessly connect to an ecosystem of digital services and data insights that was never possible until now [

big data in retail]. Within this network, Li & Fung has the challenge to remain relevant both for clients and partners, building the right solutions and the right incentives. Therefore, supply chain of the future is built on two pillars: business model innovation and sustainability.

The first imperative is to refocus the ecosystem according to the new challenges. Strategic moves are in the direction of streamlining operations, diversifying sourcing to other countries besides China and make use of technology, such as in 3D apparel design, to speed up the process end-to-end starting from design and sampling. The strength of the ecosystem is to make the strategy work, bringing together ideas, expertise, and a diversity of perspectives from

across the supply chain. In this direction, Li & Fung partnered with companies completely outside their field, nontraditional players who force to rethink the existing strategy and value chain. For instance, they work with Singularity University and MIT’s Industrial Liaison Program to foster a culture of innovation; they included in the ecosystem First Insight to combine the partner customer analytics with Li & Fung’s digital fitting and 3-D animation technology.

Speed and open innovation are not enough if not grounded in a culture of sustainability. The Supply Chain of the Future has started from the evolution of the former company purpose statement: “improving the lives of a billion people along the supply chain” including the aim “starting with our own.”

The Group holistic Sustainability Strategy is not new. It started in 2009, the year of the Foxconn suicides in China, with the aim to formulate an integrated strategy to address ESG in a manner that creates solutions and value for all LF stakeholders [

integrating ESG into corporate strategy]. Sustainability is integrated into operations and along the value chain. It becomes a fundamental part of the value proposition to clients and partners. Actions are aligned under four pillars: Supply Chain Sustainability, Engaging our people, Our Communities and Managing our Footprint.

From the organizational standpoint, the sustainability strategy is implemented, thanks to two actors:

- the Compliance & Sustainability team made of 30 people across 12 countries is responsible for overseeing vendor compliance operations. It works with all customers to strengthen compliance and sustainability performance, and maintains its independence from external and internal stakeholders by reporting to the Group Chief Executive Officer;

- the Li & Fung Foundation helps employees contribute to external communities by providing resources and support for volunteering, sharing knowledge and skills, and raising funds for initiatives, campaigns, and disaster relief. Each activity is tracked to measure the inputs, outputs and outcomes.

The supply chain is obviously the main focus of the ESG initiatives; and here, the pillars of the Group approach are three: safe workplaces, human rights, and environmental resilience with performance indicators that support Li & Fung’s contribution to UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). These objectives are achieved, thanks to a range of initiatives in the area of training, community engagement, and building a culture of positive effect.

- As Li & Fung is connected to thousands of retailers and suppliers, it uses all the information and resources in their ecosystem to help customers and suppliers learn faster from best practices and survive crisis. The company supports suppliers to continuously improve their performance by providing tools, training, and guidance to further safe workplaces, respect for fundamental rights, environmental resilience and a high-level of business transparency and ethics along the supply chain.

- Community engagement is a second driver for improving the Group sustainability performance. Community engagement helps first to carry out employer branding, attracting and retaining employees; second, it helps employees better understand all local communities and their needs. Employees are suggested to act as community engagement ambassadors to inspire others, share information, connect with community partners, organize activities, and track outcomes and results.

- Last, but not the least, Li & Fung acts as a leader and activist in promoting initiative as member of several global industry initiatives to further sustainability in the supply chain. As one of the founding strategic partners of the Global Fashion Agenda and a participant in the Make Fashion Circular Initiative, it is committed to working with customers to implement design strategies for recyclability, increase the resale of used garments and footwear and the use of recycled post-consumer textile fibers.

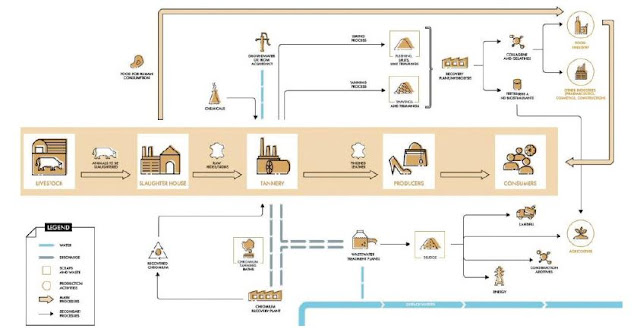

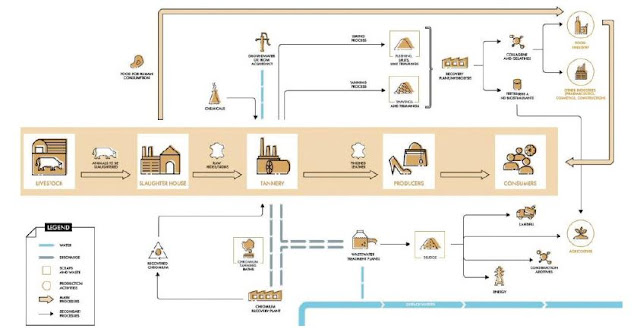

Italian Tanning. A Macro Ecosystem Based On Sustainable Development

Leather tanning is a fascinating industry that interacts upstream with the global meat industry and downstream with fashion and luxury brands. Tanning is the process of altering the raw protein structure of animal skin, preserving it from decay and turning it into leather. Leather tanning in the luxury segment is a niche industry where innovation, creativity, style and the human touch interact to create value. At the same time, the leather tanning process, due to the raw ingredients it uses (water, chemicals, raw hides/skins as by-products of the meat industry) and the

issue of waste and air emissions, has historically had a controversial reputation and a difficult relation with the communities and territories where it is located.

Italy is the European and international leader in high-quality tanning, serving mainly the luxury segments of fashion (leather goods, garments and footwear), furniture and automotive industries. The establishment of an ecosystem of actors aiming to help the industry improve its performance and image in terms of transparency and sustainability, has been crucial for the development of Italian tanneries. The Italian tanning is located within industrial districts where an industrial symbiosis takes place in the form of exchange of materials, energy, water, know-how and services among companies from different sectors. This integrated and circular industrial model enables waste production to be kept to a minimum. This approach is mutated from natural ecosystems where resources are used efficiently, so that what is waste for some organisms becomes food for others.

|

| Supply chain governance structure |

Initially, the Italian tanning districts developed locally (Arzignano in Veneto, Santa Croce and Ponte ad Egola in Tuscany – the largest in Europe, Turbigo in Lombardy, Solofra in Campania). In just a few decades, companies and institutions have been able to create an efficient and interconnected network of consortia and services for all member companies. This is an insightful example of a macro-business ecosystem led by a group of organizations whose goal focuses on helping the industry achieve a common interest. The common interests for tanneries lie in sharing data and insights and promoting best practices to improve safety and security and encourage innovations as well as cross-ecosystem actions and reporting on key issues such as sustainability [

enterprise data management]. A second common objective is sharing operations and expertise, so that organizations can scaleup their capacities for new products and services.

UNIC: from Industry Association to Ecosystem Association

A fundamental agent within the ecosystem is the Italian Tanners’ Association (UNIC), which has been supporting its associate companies since 1946. Not only does the Association promote the interests of the entire industry, but it also represents the industry with different stakeholders, boosts innovation, enhances both its social and environmental roles and sets up commercial services companies that are functional to the sectorial market. The Association is therefore playing an important role in making the tannery world-transparent and responsible, creating value for all members of the ecosystem, fashion and luxury brands downstream included. The 200 member companies are all part of the Association governance board; they are competitors, but they easily cooperate within a neutral environment according to a coopetition approach, which is typical of successful Italian industrial districts. In the event of a company financial crisis, the company is not left alone but is acquired by other companies so that the precious know-how does not disappear. Recently, private equity firms and luxury brands made acquisitions in the industry as the

financial margins of tanneries are attractive and excellent, and sustainable suppliers are very much in demand to reduce the reputational and strategic risk for luxury brands downstream. This represents the best case of alignment between the interest of investors and industrial companies.

A keyword for the future of the ecosystem is regeneration. The Italian company SICIT is an example of global excellence in the field of regeneration and one of the pioneers of the circular economy. It was one of the first companies in the world which, through a process of hydrolysis of residues from the tanning industry, created high-added-value products for agriculture (biostimulants) and plaster industries (retardants). The business model is also innovative: a consortium among public and private organizations. Since June 2020, the company has been listed on the MTA (Italian Equities Market), Star Segment, of Borsa Italiana, and tanners decided to invest and become shareholders. This is the best-case example of public governance of the local community with the support of private companies.

The three challenges for building a transparent and sustainable ecosystem

The Italian Tanners’ Association addresses all the most important challenges connected to end-to-end leather processing. There are many misleading communications about leather and leather substitutes and the debate often tends to slip into different territories such as personal ethics (eating animals), whereas the topic of sustainability in business should be discussed in terms of general standards and regulations. The tanning industry is actually a circular industry, ante litteram, as it has always upcycled the waste of the meat industry, the raw hides and skins (transformed into leather by the tanning process), in accordance with the idea that you should throw away nothing of an animal. With no tanneries, there would be a crucial issue in terms of waste disposal in the food pipeline, loss of valuable material and reduced margins for the meat producers upstream in the pipeline. Not to mention that fashion is making use of synthetic alternative options, which derive from plastic and other nonrenewable sources.

Terminology is essential here: vegan leather, eco leather and techno leather are very often definitions for synthetic materials or non-sustainable processes, and there is a lack of transparency about how these alternatives to leather are produced. The latest Italian and European legislation have contributed in defining what real leather is and what is not. In this process, educating final consumers about the benefits of real leather is key. Industry communication has so far been quite technical and detailed, while it should become more emotional and engaging through an unconventional media planning addressed to different audiences. Since 2002, the Association has published a Sustainability Report every year, initially targeted at a limited audience, and which now aims at addressing all stakeholders. The Association is also launching a series of communication campaigns directed at improving the image of Italian leather.

A second challenge for the Association is the tanning process sustainability and transparency. The meaning of sustainability for Italian tanneries is presented below and is based on the interplay of economic, environmental and social goals. Environment means first water treatment. Tanneries need water and they have always developed in proximity to rivers and lakes. But water is also the most precious resource for communities and for the society at large. Water pollution is of course a huge problem worldwide, but since the 1960s, Italian tanneries started developing consortia to collaborate for environmental support with the creation of the first waste water treatment plants long before industry regulations were established.

|

| Governance in supply chain management |

In addition to water, tanneries utilize chemicals with all the related issues regarding environmental effect. In recent years, there has been a great improvement in safe chemicals, better remote management of chemical plant safety and a decrease in waste management costs. All these improvements have a cost, and investments made by the tanneries should be covered by the fair price of their products [

price optimization].

And here comes a third challenge for the Association: the economic sustainability of the system. The sustainability challenge can only be managed together with client brands through greater collaboration. Buying offices of luxury brands negotiate with tanneries on prices of leathers and skins according to certain sustainability grids, evaluating guarantees on materials with potential risks in terms of sustainability [

premium pricing strategy]. But too often these prices do not consider the cost of sustainability of upstream phases [

penetration pricing strategy]. A remarkable percentage ranging from 4% to 10% of a tannery’s total costs goes into environmental compliance. Small companies may have difficulties in understanding the need to improve sustainability in their process as it requires large amounts of financial, human and organizational resources [

different pricing strategies]. The Association helps them in terms of awareness, education and the right tools to improve their commitment. But the “sustainability of sustainability” should become a wider concern end-to-end. Fashion brands downstream could reward leather quality in a holistic sense, also considering that mature consumers look for better quality and greater transparency [

how to fight a price war]. The downside effect of a lack of collaboration within the leather pipeline is the risk that consumer perception and under-standing of leather quality disappears due to an excess of misleading communication, with a disruptive effect on the entire ecosystem end-to-end [

pricing strategy].

COMMENTS