Aspire Thought Leadership! Wondering about strategy in supply chain management? Find out more on how fortune 500 companies use this approach.

In the last few decades, the term strategy in supply chain management has gained mounting relevance and popularity in business literature and media. However, most marketing and brand executives spend little time thinking about their company’s supply chain. The brand promise is about delivering the right product, to the right place, at the right time. Supply chain capabilities can make or break the brand ability to fulfill that promise. It is the engine that connects consumers to their favorite products. The supply chain’s mission today is to enable trust, transparency and speed, helping create loyalty to the brand. We believe that learning to understand and appreciate the role played by the supply chain can ultimately make the role of brand managers and marketer more effective and innovative. Branding the supply chain means using the supply chain as a driver and differentiator for the brand story to inspire loyalty and secure sustainable growth.

Strategy in supply chain management

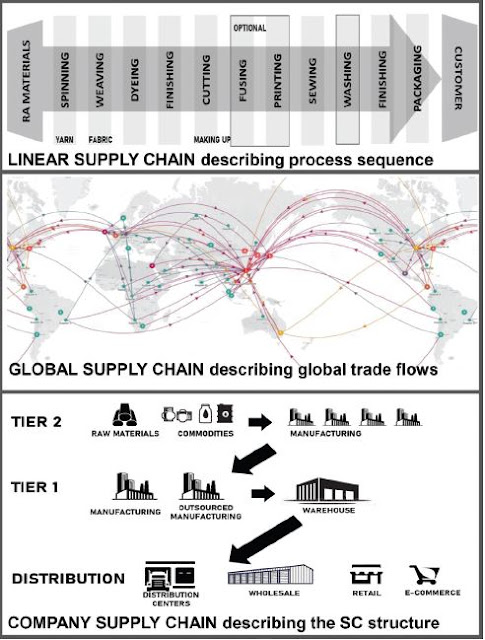

A better understanding should start from the definitions of supply chain as indicated in Exhibit 1.

|

| Strategy in supply chain management |

Initially, the supply chain term was mostly used to describe all the phases needed to go from raw materials to final products, illustrating the linear and sequential flow of stages and transformations through which a specific product is made and delivered. For a garment this means describing how the raw material is transformed into yarns, yarns woven into fabrics and fabrics sewn into a garment sold to a client with all the necessary intermediate finishing and value adding steps.

A second use for the term supply chains, as plural, pictures the aggregate trade flows describing where an industry as a whole, or a generic type of product, are produced and traded around the world. Globalized manufacturing in the mid-1990s popularized the term supply chain in its macro dimension of trade flows: China’s yearly exports to the USA went from $45bn in 1995 to over $280bn by 2006.

The third and by now a widespread application of the term refers to the supply chain of a specific company and is often associated to the term management. Supply chain management is concerned with getting a product to the right place at the right time. It describes how a specific company designs and manages its supply chain as an expression of its decisions about “make or buy” business activities [business agility]. Making products inside company’s facilities or outsourcing to external manufacturers? Vertically integrate the sourcing of materials and components or buying the services of an external sourcing office? Today, as a consequence of the proliferation of opportunities in terms of buying, sourcing and manufacturing on a global scale, the simple “make or buy” option has become extremely more complex and articulated.

Nevertheless, the supply chain’s role in making end-to-end processes and strategies work effectively is clear as it embraces within a single perimeter a vast network of internal and external activities and actors: vendors of raw materials, producers and convertors of components as well as finished parts and products, the logistic tangles of shipping and transportation as well as all warehouses and distribution centers till the final store delivering products to end clients.

The effective design of such supply ecosystems has indeed proved to be a major source of competitive advantage as in the examples of fast fashion retailers such as Zara or H&M. These players have disrupted the fashion industry, thanks to the unprecedented effectiveness and responsiveness of their innovative supply chains. In a time when no other accessible fashion retailer was even considering reshoring production away from low-cost countries, these players developed their regional sourcing in proximity to speed up their response to customer preferences changes [customer value proposition].

Important to note, entire industries such as apparel, food and electronics have lately increased product variety to offer more options to retailers and final customers. While the “newness imperative” has shortened products’ lifecycles, the quest for transparency has simultaneously increased the pressure on disclosing how activities are managed “behind the scenes”. Having to cope with all these disruptions, supply chain definition and scope have also considerably changed, as we will discuss in the next paragraph. The supply chain today is much more than a sequence of activities and boxes; it is a value generator as well as a strategic differentiator and, above all, it has the power to touch and transform people’s lives. However, there is still a long way to go. It is estimated that sixty percent of global trade is now being driven by big business, which too often uses business models based on exploitation and abuses of human rights in supply chain1; companies evaluate and report about social issues within their supply chains not what is most meaningful but just what is most convenient, information that they have ready access to and are willing to disclose.

Let’s now try to deep dive into the key factors behind the recent evolution of supply chains that are creating opportunities as well as new challenges for consumer brands in terms of ESG compliance.

Transformative forces behind strategy in supply chain management evolution

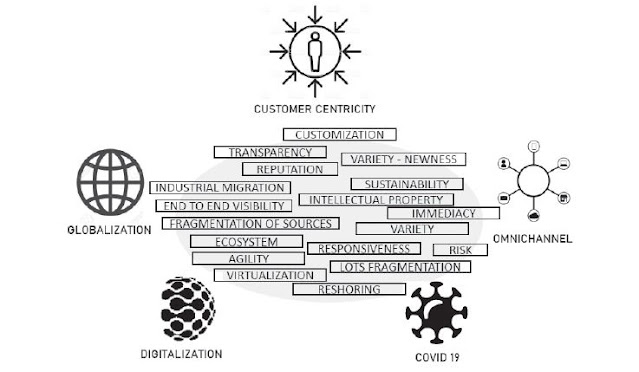

Complexity in terms of organizational perimeter, articulation and geographical configuration is considered as the major force affecting supply chains’ evolution during the last few years. Exhibit 2 captures some of the buzzwords that have lately tangle-like characterized business conversations about trends in the supply chain. Some macro trends that were already in place such as customer centricity, omnichannel and digitalization, have been accelerated as an effect of the pandemic, and they have all converged in an unprecedented quest for flexibility, speed and accountability.

|

| Strategic supply chain management |

In the last few years, economic power has continued to shift from sellers to consumers. In the consumer-to-consumer economy, individuals and communities are empowered by a variety of new communication tools and touchpoints to interact with brands and peers. Brands are increasingly competing on “who spoils the customer better” ground. More variety? More newness every week? Limited event editions? Customization? Personalization? Same day delivery? Unlimited returns? All such dimensions have great and sometimes neglected effect on how supply chains are designed and perform. Within a customer-centric approach, supply chains need to find ways to make themselves more visible and accountable to the final consumers.

Globalization

Since the mid-90s, the opening-up of new international sourcing sites and the progressive reduction of trade barriers have produced an unprecedented transformation of traditional supply chains’ geographical spread and configuration. Western companies have relocated large portions of their industrial activities to low-cost countries through complex and fragmented supply chain architectures. Textile and apparel, toys and consumer electronics are the most evident examples. In a few decades, China has acquired the role of “factory of the world”, becoming the manufacturer for many industries, serving half of the entire global demand. The pure search of the lowest cost has been recently showing its limits though. With China’s increasing labor cost, many labor-intensive productions have migrated to more competitive sources such as India, Vietnam, Cambodia or Bangladesh [how to fight a price war]. Recent trade wars have also contributed to increase the risk of over-spread supply chain configurations. Contemporarily, the explosion of supply chains’ complexity, fueled by product variety proliferation and shortening of their lifecycles drastically reducing planning visibility, has forced all types of organizations to re-consider the trade-off between production cost and market responsiveness [pricing strategy], strictly related to the issue of work in capital optimization and risk mitigation. The fashion industry, for instance, has eventually realized that remote sourcing heavily affects its capability to increase sales at full price [retail pricing strategies], thus reducing unsold inventories [premium pricing strategy]. Global sourcing may indeed minimize production costs, but moving parts around the world generates other costs and takes time while holding up capital [different pricing strategies]. Many companies had indeed rushed into sourcing markets they didn’t understand (in terms of local regulations, social values, worker safety standards) without considering the related logistics costs and the strategic implications of such choices on their long-term flexibility, resilience and reputation. Let’s face it: the relentless pressure to cut prices [strategic pricing] has led to the creation of supply chains and business models that no-one properly understands [penetration pricing strategy].

Digitalization

All these disruptive processes could not have taken place if not supported by the digital transformation strategy. Consolidated by the current widespread adoption of Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) software, data management and systems integration are today the backbones of supply chain management and the bases of its strategic development [enterprise data management]. Modern supply chain software covers a wide range of functionalities from design to planning or logistics, from execution to control. Increased end-to-end visibility and traceability are also an effect of digitalization [digital disruption]. Both provide each member of the chain potential access to real time data, thus creating the conditions for greater responsiveness in adjusting to inventory shortages or overages, modifications in orders and changes in the availability of resources and production capacities. Supply chain digitalization, today enhanced by– Internet of things (IoT) – embedding objects, machines and processes with sensors – integrates physical processes with digital data creating a minefield of new optimization opportunities. New advancements in the areas of Artificial Intelligence in business (AI) and predictive analytics boast forecasting and planning capabilities. Cloud computing and storage provide unique opportunities for accessible data management adoptable by organizations of any size [big data in retail].

Although data management has thus taken the central stage in the area of supply chain management, visibility still remains a critical challenge for many organizations. Data management should indeed play a critical role, but if not properly governed and directed, it generates an explosion of information often overwhelming organizations.

Digitalization will hopefully play a role in accelerating transparency through the adoption of technologies aimed at single product traceability. New-generation RFID tags provide a unique identity to each individual product, recording all steps and stages on its journey to reach the final consumer. The blockchain technology supports certified tracing. These technologies combined with new-generation networks, widespread connectivity, applied Data Science and AI, cloud storage and pervasive IOT will soon allow the creation of networks and platforms gaining incredible scope and impact. It is in this perspective that many opinion leaders identify in technological and digital innovation the accelerators and enablers of the sustainable and transparent supply chains of the future.

Omnichannel

The progressive shift from the multichannel dimension, in which companies operate along parallel commercial channels and silos, to the omnichannel approach has completely transformed the management mindset: data and integration are the drivers of higher effectiveness and efficiency [mindfulness in the workplace]. Multichannel strategies used to focus on sales activities optimization within each channel; an omnichannel strategy concentrates on customers’ specific requirements, on total revenues and on creating a unique seamless experience [integrating ESG into corporate strategy].

In a supply chain perspective, the most direct effect of omnichannel has been on inventory management, logistic and fulfillment activities. In order to respond to customers’ expectations, no matter the channel and location of stocks, the integration of different inventories allows to achieve real-time visibility and speed. With the growing fragmentation of order sizes, most companies and brands have been forced to redesign their logistic setups and distribution and fulfillment centers to deal with the fast growth of small parcels. It is worth mentioning the case of Farfetch.com, the Luxury e-tailing platform that has built-up an innovative business model by leveraging on the store inventory hold by a multitude of independent multi brands retailers around the world and making it accessible for orders online.

In addition to inventory management omni-channel has affected the supply chain configurations. As new services are offered to consumers such as Buy online pick up in store (BOPIS), the logistic equation “Inventory cost – Facilities cost – Transportation cost” has become considerably more complex to assess and optimize.

Pandemic and re-shoring

Only time will allow us to fully understand the Covid-19 pandemic effect on the business at large. What is already quite clear is that market and technological trends already in place are accelerating. By speeding up e-commerce’s growth, the lockdowns were accelerating the need to respond fast to an increasingly fragmented demand. By increasing the risks associated with distant sourcing, the lockdowns increased the benefits of re-shoring or nearshoring initiatives, in other words bringing productions closer to their consumption markets. Benefits of re-shoring are the potential reduction of time – to market and a prompt reply to shifts in demand, thus reducing the risk of inventory obsolescence and fluctuations in exchange rates. Other indirect but not less important sourcing risks are mitigated by re-shoring such as intellectual property infringement and lack of transparency in the supply chain that might end up in brand reputation issues. Global trade flows and supply chain configurations will also eventually reflect individual governments’ orientation to global trade and their trade and tariffs regulations. The recent “bring production back to the US” political initiatives or the relaunched EU trade agreement for textile, that aimed at eliminating duties among 20 out of 24 of the pan-Euro-Med (PEM) trade zone partners, are expected to represent key drivers shaping the future of global supply chains. Last, but not the least, by forcing commercial ceremonies such as the seasonal fashion shows and buying sessions to turn digital, the Pandemic is rapidly contributing to weaken even further the traditional fashion cycle.

The outlined concurring forces have generated two effects on supply chains:

- Structure. From a wider perspective, the supply chain structure has evolved away from once linear and sequential logics toward networked and extremely articulated setups that we could define as eco-systems. Eco-systems immersed in larger ecosystems and competing with other ecosystems.

- Role. From a company’s internal perspective, functions and processes once seen as separated have progressively merged. By encompassing procurement-buying, planning, product development and production, quality management as well as sourcing and all logistics and storing activities, the term supply chain has been increasingly associated with the role of “orchestration”. A kind of superior role that spans end-to-end processes, orchestrating the contribution of many functions and actors until recently operating quite autonomously, often sequentially.

From being considered an executor, the supply chain has become a critical strategic facilitator called, while still carrying over its traditional role, to be ready to adjust to the new strategic imperatives of being resilient and agile, and become above all a brand value generator in the era of transparency.

From risk mitigation to value generation

Because of its role of orchestrator of virtually all physical activities in an organization, the supply chain has always posed some risks of failure, as with any human and business activity. Mitigation plans, what-if’s, scenario analyses and contingency plans are all terminologies describing how articulated supply chain risk assessment and mitigation have become in most companies. Exhibit 3 introduces us to the two typologies of risks, strategic and operational, which companies are called to cope with.

|

| Strategy of supply chain management |

Operational risk

Operational risks might be associated with performance mismanagement (our forecasts were wrong, our systems broke down, we did not properly monitor our inventory levels because of an organizational glitch, our supplier’s factory was devastated by a fire and we did not have a plan B…), or related to the financial dimension (raw material exchange rates climbed, new regulations or duties were introduced, credit crunch affected financing our cash flow..), while the impact of natural events on physical assets (flooded warehouse, pandemic…) is also considered an operational risk. The explosion of the complexity that the supply chain is called to manage has clearly made preventing or mitigating such operational vulnerabilities more articulated, but still demanding the application of management logics within the conventional engineering-like, measurement-driven culture of supply chain management.

Strategic risks

What is changing considerably, taking supply chain management out of its comfort zone, is the strategic risk dimension. Risks with the power to dramatically affect the brand reputation and equity in two ways.

- On one side, the growing likelihood of disruptive scenarios rapidly transforming the industry and its competitive landscape: the unexpected impact from the adoption of new technologies, the sudden rise of new trade barriers and regulations are all risk forces capable of derailing a brand or company economic sustainability, business model or strategic outlook. To mitigate such disruptive scenarios, supply chains are called to be agile and resilient.

- On the other side, the quest for “transparency” has brought over an altogether new weave of reputational supply chain risks. What was business backstage is increasingly becoming a window exposed to public scrutiny. A single picture taken in a remote and obscure sweatshop with a child sewing a garment may pop-up in no time on social media, dramatically exposing the associated brand. A television reportage in a farm where chemicals and pesticides are used with no rules can quickly expose a large food retailer and annihilate all its investments in “bio” products. Reputation-killing issues such as minority discrimination and the existence of an unethical and hostile workplace at suppliers can make the brand value evaporate in just a matter of seconds in the eyes of customers and stakeholders, as well as exposed bribes to shady government officials or the discovery of salmonella traces in spinach.

The reputational risk dimension represents the most pragmatic call to action for companies, brands and retailers. With so much brand value being derived today from difficult-to-quantify assets and intangibles, supply chains’ reputational risk can no longer simply rely on an old-style crisis management [value matrix]. But how then, should the supply chain mitigate these strategic reputational risks?

Central to the thesis brought forward in this book, the answer we identified focuses on moving from a reactive-defensive to a proactive and constructive approach. By entering into the strategy realm, the supply chain must integrate its views and logics with the other corporate perspectives. For instance, supply chain management must become familiarized with the logic of relevance, what really matters to the company stakeholders, and from there understand how and where it can contribute in value creation. Considering the typical supply chain measurement-driven culture, it is from its metrics that such a perspective broadening must start.

Quite intuitively, redesigning the supply chain to achieve full compliance and transparency makes compliant companies less cost-efficient versus noncompliant competitors. Compliance is expensive. How then to overcome this? Companies should start adopting a more comprehensive approach in measuring supply chain performance, integrating the traditional cost performances (the production cost, efficiency and productivity) with more innovative non-cost measures such as reliability, responsiveness and flexibility.

We suggest that the two additional non-monetary dimensions should be integrated for the evaluation of supply chain contribution to value generation and risk mitigation: the cost of opportunities and effect on brand reputation.

- The opportunity dimension: companies typically seek to simultaneously optimize multiple objectives in their supply chain management practices. They might, for example, strive to lower costs while also improving product quality. The costs and benefits of every option available must be considered and weighed up against the others. To use a fashion example once again, by tapping into the lowest unit cost available, a retailer can decide to source a certain order from a remote location. But this decision is also associated with longer delivery and shipping times that must be taken into consideration. The key questions to be asked are: what business opportunities am I losing by going remote and ordering large volumes and waiting for a long time, therefore making my proposition more rigid and prone to heavy discounting?

- The reputational dimension: following on with the previous example, the same retailer must also include in its decision process the reputational risk considering the possibility that its remote supplier allows illegal working conditions in its factories. The key question to be asked here is: what is it worth to risk being exposed on the misconduct of my remote supplier?

By being called to play the strategy game, the supply chain needs to broaden its perspectives and focus on both tangible and intangible downstream value it can contribute to create for the consumer and the stakeholders. Paraphrasing McLuhan’s famous “media is the message” statement, we could say “the branded supply chain is the product”.

For companies having a supply chain executive who fully understands the supply chain’s strategic connections to the company’s success has become of paramount importance. Similarly, more understanding of the supply chain logics is increasingly critical for other top management roles. Last, but not least, a culture of transparency might attract and retain talents as the new generations want to work at trustworthy, ethical companies. “Nearly 90% of the questions job applicants ask us relate to sustainability and ethics issues” said Antoine Arnault, General Manager of Berluti and image and environment Director at LVMH Group.

Supply chain finance 2.0

Supply chains are getting multilayered and interconnected, and many rely on a fragmented network of small-sized enterprises as in the case of fashion and luxury or the food chain. Within these fragmented networks supply chain leaders or “pivot” not only build stable vendor–supplier relationships, they must also foster a collaborative approach with other key stakeholders and possibly build value for the entire supply chain. A leader usually relies on a strong brand awareness and image in its market, sizable revenues and export shares, good economic results and a sound financial profile. As a consequence, its credit profile is strong, enabling access to wide financing opportunities, both in the banking system and in capital markets. Its strategic suppliers and partners are often smaller in size with unstructured controlling and reporting mechanisms, characteristics that lead to a weaker credit profile and limit their access to financing opportunities.

Supply chain finance is a set of solutions enabling strategic suppliers to benefit from the stronger rating of their pivot in the supply chain, who can access capital at a lower cost. The pivot is accountable for the credit process: the lender – a bank or a fintech company – assesses the credit profile of the “pivot” and extends its “credit value” to its suppliers. The ultimate financial risk depends on the pivot as the commercial success of its offer reflects on all upstream players.

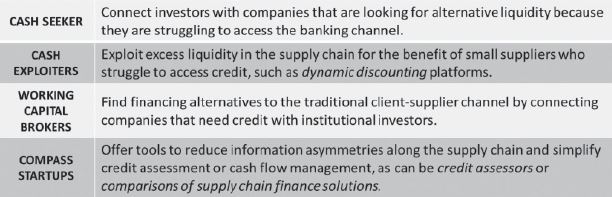

In the last few years, many more supply chains financing tools have been launched by the recently developed fintech industry.

With brands and retailers called to be accountable and transparent, supply chain finance represents a critical tool for leading companies to deploy a simple though effective tool reinforcing partnerships within their supply chains.

The pandemic has disrupted many supply chains with upstream suppliers left in dramatic financial difficulties; supply chain finance does represent a unique opportunity not only to strengthen the buyer–seller’s bonds within supply chains, but simply to give to weakest suppliers a chance for survival.

Some industries have been more reluctant than others in adopting these tools. The stability of relations within supply chains does have a relevant effect here. Fashion brands, for instance, value agility and flexibility rather than stability in partnering with suppliers in order to be able to better follow fashion trends and also maintain some negotiating power. A second reason for the scarce adoption is related to silos within most companies: suppliers’ issues are heard by the supply chain manager or the chief operating officer, whereas financial decisions are made by the Chief Financial Officer, and many times there is a lack of communication among the two functions.

How Fintech is changing traditional supply chain finance

The supply chain finance market has been steadily growing worldwide. According to the recent data3, the Italian market is characterized by an average days sales outstanding (DOS) of 74 days in 2018, the longest payment terms in Western Europe. Therefore, the total volume of trade receivables in Italy is estimated at EUR 637 billion, higher than Germany (582 billion), France (529 billion), the United Kingdom (411 billion), Spain (341 billion) and the Netherlands (170 billion). This situation offers significant supply chain finance opportunities to Italian companies.

In Europe, the banking system is still the larger provider of finance, with fintech catching up. Outside Europe, Chinese supply chain finance market is estimated to reach ca. USD 2.7 trillion by the end of 2020 and fintech and eCommerce platforms are exceeding the traditional banking market in size. Covid-19 will probably have dramatic effects on the economic situation and the increasingly global and interconnected supply chains will be heavily affected.

From the credit crunch of 2008, the banking system has been unable to fully satisfy the financing needs of the system in spite of the increasing support offered by Central Banks around the globe who have been injecting huge liquidity in the system.

Credit tightening was a significant consequence of Basle III regulations that require commercial banks to accrue capital charges depending on credit ratings of their borrowers, pushing banks with limited access to capital to “flight to quality”, i.e., lend money mostly to highly rated companies, penalizing riskier low-rating corporates, often the smaller ones or the ones which are financing innovative, and therefore risky, projects. In addition to Basle III constraints, the current existing high stock of nonperforming loans further reduces the capability of banks to lend money.

A relevant response in the financial industry to the banking credit crunch was the development of Fintech startups offering new models and solutions for supply chains, raising cash from crowd-funding platforms offered by investors who look for nontraditional investment opportunities.

While commercial banks are dealing directly with customers and managing the full credit process, different specialized players operate in the unregulated nonmature Fintech market as outlined in the following exhibit.

|

| Strategic sourcing in supply chain management |

A wide range of solutions

We briefly review the different supply chains financing solutions going from those offered by the traditional banking market to the new solutions offered by Fintech companies.

Reverse factoring

Until recently supply chain credit was a synonym of reverse factoring. This tool allows suppliers financing by assessing the risk of the supply-chain pivot, who is willing to support its strategic suppliers by making their business more stable and retaining them. It is a “win–win” situation where each actor gets what he needs: the supplier is paid quicker and at a lower cost without delays, the supply chain leader can obtain a discount on its supply, the bank/fintech has its own remuneration. Facilitated by the wider use of electronic invoicing, fintech platforms have recently replicated this successful tool born in banking. The advantages of fintech reverse factoring are an automated and leaner approval process, a lower and more transparent cost structure and quicker feedbacks.

Advance invoice, factoring and evolution into invoice trading

Advance invoice is a short-term financing provided by a commercial bank and guaranteed by trade receivables of the borrower. The borrower discounting the invoice receives a percentage of the nominal value of the receivable (the difference to nominal value covers interests and fees). When the receivable is paid, the bank recovers the full amount. Usually, the bank runs an assessment of the borrower’s creditworthiness and fixes a global limit.

With factoring, the borrower sells its receivables to a specialized financial company (the “factor”) for an amount net of interest and management fees. It can be carried out with recourse (pro solvendo), such as a bank advance, without eliminating the risk of insolvency of the debtor, or without recourse (pro soluto) where the costs of factoring rise further.

Advance invoice and factoring have undergone a relevant evolution through fintech platforms, where companies can sell their trade receivables to specialized investors: the invoice trading. These platforms can act as brokers, as a marketplace to match supply and demand or can invest directly alongside other specialized investors. Some platforms allow investment by both retail and institutional investors, others are accessible only to selected investors.

With invoice trading, a company seeking financing can offer its receivables up for sale on a fintech platform, where qualified investors carry a competitive auction to purchase them. The sale price optimization is the final result of the re-launches offered by participating investors. Thanks to this mechanism, the company can collect the best negotiable price reducing the discount on face value as much as possible, while the fintech platform collects fees for the intermediation. Fintech platforms create a direct link between investors and corporate. Because platforms mainly evaluate the debtor’s creditworthiness and not that of the supplier, Fintech also offers a liquidity solution to individuals to whom traditional banks would deny credit.

Innovative Fintech supply chain finance tools

Besides offering an evolution of existing banking tools, Fintech expand supply chain credit beyond invoices with tools guaranteed by orders, stocks and investments. Purchase Order Finance, for example, foresees the use of an order received by a customer with high creditworthiness as a guarantee to obtain financing: compared with traditional solutions, the focus of financing shifts from invoices to orders supporting the purchase of materials or products necessary to activate a production. Another tool, Dynamic Discounting, involves prepayment against a discount proportional to the days in advance, which allows financing actors in the supply chain without involving third-party lenders. Finally, Equipment Financing, a set of financial instruments to support the purchase of durable assets is worth mentioning.

Fintech innovative supply chain finance: the Credimi case

Credimi is one of the most successful Italian Fintech initiative and a pioneer of fintech supply chain finance on the Italian market: founded in 2015, to date it has lent more than €1bn to European SMEs. The massive requests for new financing received by the platform during the Covid-19 emergency – more than 2,500 requests per month is a clear sign of an increasing need for innovative financing by SMEs. Credimi’s core competences are a mix of advanced automated financial modeling and human judgment: lending and scoring process are executed online. Furthermore, distribution is without a branch network.

After customer’s on-line application, Credimi scoring process includes two automated steps and a final validation by an analyst. In the first place, “Octopus” algorithm analyses applicant’s credit risk by searching information through a number of sources, including “Centrale dei Rischi”, news and publicly available financials. On average, about 30% of the applications go through the first screening to the second phase, where “JessicaF” app scouts potential frauds from different sources. The third step – the Know Your Customer phase – is performed by an experienced analyst, who takes the final decision on the application. Over the years, the loss ratio has been around 1% (unchanged even after the pandemic) thanks to the proprietary scoring system and the granularity of the portfolio (average exposure is around 100k in business loans and 400k in factoring). Beyond factoring a significant share of financings are lent as “Reverse Factoring without recourse”, a supply chain-financing tool. Credimi preventively assesses selected “Partners” of Industrial Groups (about 10 of them have been served over time, with hundreds of suppliers involved) and defines related plafond and thereafter discounts the receivables of Partners’ suppliers, based on the defined plafond.

COMMENTS